The dawn pressed its blue face against the frosted glass and the boy sat up, staring towards the door, quiet. If this was a dream it was an unkind one, for the moment his eyes went towards it, he was paralysed, at its mercy. Whatever was coming for him had all the time in the world, whereas the boy only had the rest of his life.

The boy was only nine the first time he saw a corpse; a woman, young, lying in a busy street, puréed brains spilling from her head. The father forced him down below the back seat with one hand, the other gripping at the wheel as the car slowly filtered through the mass of feral onlookers. But it was too late for the boy, he had seen enough to fuel his nightmares for many years to come. Seeing something like that changes a person, especially if they’re a child. They get an appetite for it, not because they like it but because their mind doesn’t understand it and demands to see more, demands to learn more. The boy was like that now. Every day from that day forth, when they drove him home from school, the father would order him below the seat, but still the boy would peek from time to time, and hope to see something worse.

They wanted to leave the city, the family, for many years now. The place was eating itself. Suburbia had become Sodom and Gomorrah, but there was no god now to destroy it, to wipe it clean. Violence was the only currency, degeneracy the only language. But the father hadn’t been so lucky with his work, and moving out to the boonies was impossible for now. With the mother’s wage and the father’s subsidy, they were able at least to be away from the city centre, and have something like peace whilst living on the outskirts. Still, they lived in the shadow of the great wren, and every year the outskirts lost more territory. It was unsustainable. Living was outdated, surviving was fashionable.

The father was paranoid. In truth, he always was in some way – you only had to see the way he kept his wife so close to him to know, not due to his affection for her, but because of some sense of possession. The city had not had a good effect on him; each month it seemed to drain some more rational part of him and replace it with hysteria. When the car reached the driveway, he was the first one out, and when the door to the house was unlocked he was the first one in, all the while checking over his shoulder. When he was satisfied that every door and window between them and the terrible world outside was secured, he would lock himself away inside his drawing room, and spend hours upon hours consuming news reports that confirmed his worst fears. You could hear it echoing throughout the house, and when there was nothing to hear there was something to read. “Boy, 15, stabbed to death”, “Sex crimes on the rise”, “1 in 8 dead by Christmas”, “Civilians caught in gangland crossfire”, etc, etc. “Family of three murdered in their home” was the headline they were waiting for, then the father would be right, and his madness would cease to exist. Until then, he was to them what the city was to him, and no less violent.

They were sure this was the night it would finally come to pass. It started like any other, when they pulled onto the driveway and the father took to the house like an impatient dog, leaving the other two to lock up. The mother split the grocery bags between herself and the boy, and ruffled his hair when he assured her he was capable of carrying them. In the kitchen they discovered that one was unaccounted for, and the boy remembered.

‘I think I moved it so I could fit under the seats, Mama.’

She ruffled his hair again, and asked him to fetch it for her so she could start on dinner. The keys were handed to him, heavy in his trembling hands.

‘Make sure you lock the car up afterwards, honey,’ she told him, and the boy nodded.

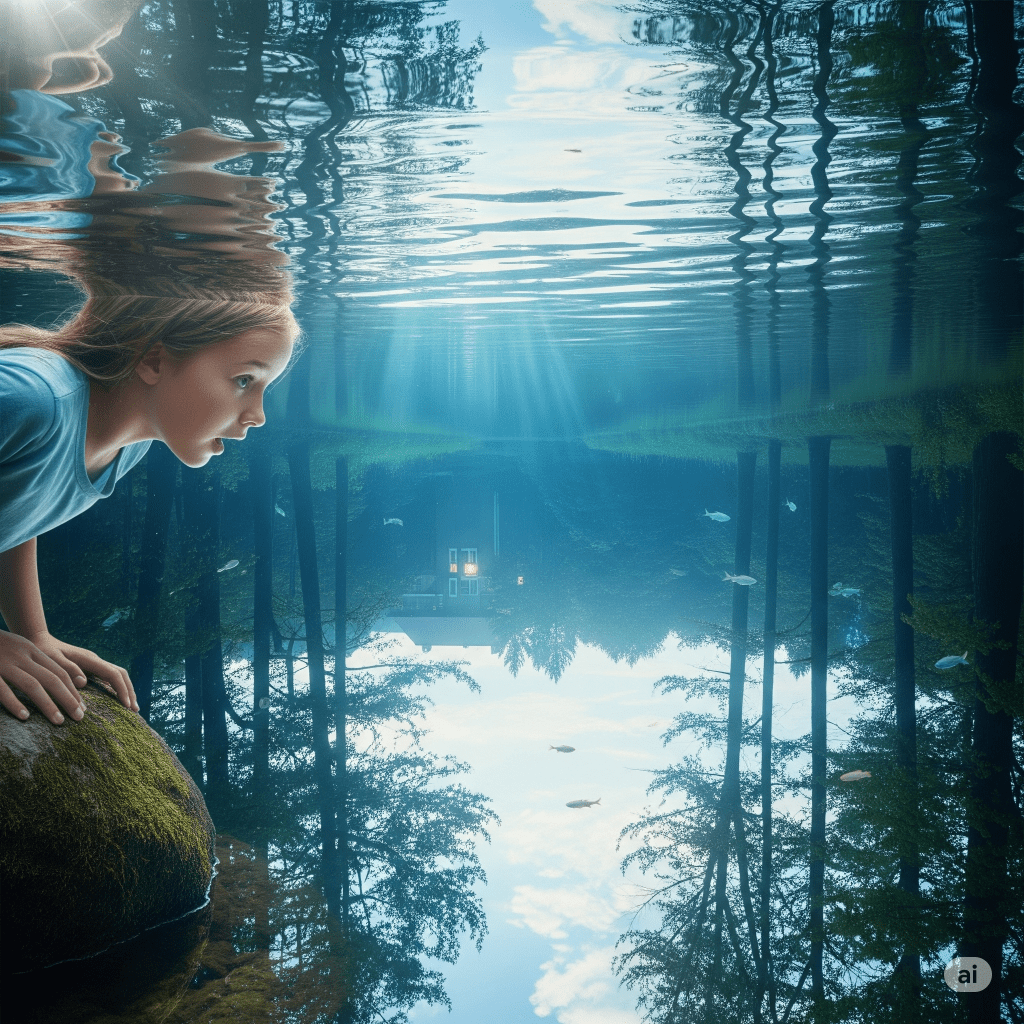

The boy stepped out into the warm evening air, sky burnt and oily above him, and looked yonder to the city. It looked almost lonely from over here, no more dangerous than himself. As the sun went down, the lights of the city dazzled, tantalizing, luring him towards it like a deep-sea fish. The boy wanted to run to it, he wanted to see what horrors may be lurking there under the gloss of the lights. He wanted to see more bodies like the one of that woman, wanted to see what humans could do to each other. The sounds of the wind chimes snapped him out of it, and he remembered the bag and how long he had been standing out here.

It was where he suspected, sides ripped but still holding the contents together, wedged beneath the driver’s seat where his feet had kicked it to. He fished it out and locked the car, checking twice, three times that it was indeed locked, before going back to the house. A stocky man stood in the doorway of the next house, a neighbour the boy had seen only half a dozen times and certainly never spoken to. He had a thick, grey beard that covered most of his face, and hair to match, making him look apelike. The man was affixing something above his door, a small silvery fish of some kind, one nail to the head and another to the tail. He hadn’t noticed the boy to this point, and the boy didn’t want him to. He went up to his own door, watching the man, looking away only briefly to slide the key into the lock and open it. To go into hell to escape the devil. But when he looked over his shoulder again, the neighbour had not only turned his head but his body, and now stood staring straight at the boy, straight into him. His eyes seemed to hold him there, burning furiously behind the unkempt beard of his. Seconds were eternity in that stare, but the man broke it eventually with a smile. A strange sort of smile that unfroze the boy’s body and dispelled his fear. The man even gave a nod, and purred:

‘Good evening to ya. Give your best to your ma and pa now.’

The boy nodded, and dared to smile before his mother called out for him from the kitchen. When the boy looked back the man had turned towards his doorway again, making sure the fish was holding in place. The boy stepped inside the house, let the door close behind him, and carried the last of the bags through the hallway.

‘What took you so long, honey?’ she asked him, taking the bag.

‘Nuthin’. Bag was stuck.’

He turned to go, but she stopped him again, holding out a hand.

‘Keys?’

Keys! His little legs raced back to the door, a glowing black behind the glass now, daylight all but gone. He could picture the keys exactly where he had left them, dangling from the door outside the house, but when he tried the handle, it would not move. Not even an inch. That handle would not move! The door was locked. Locked from the outside!

The hallway seemed three times longer than it’d been only moments ago, and the boy shook all the way down it and was still shaking when he reached the kitchen. It was her he dreaded telling most. Beatings from him were temporary, disappointment from her left a permanent mark. But now was not the time for fear, not while something could possibly still be done. He blurted it out all at once, in case the tears stopped him, and saw the horror etch onto his mother’s face before she brushed past him and made for the door. He listened to her trying to move the handle, but knew she wouldn’t, and that was when he finally let the tears flow, unhelpful as they were, he couldn’t stop them.

She couldn’t peep through the letterbox to check the car was still there, (the father had boarded it up after hearing a story from the city of someone putting petrol through their neighbour’s letterbox), but the faintest outline of it could be seen through the frosted glass window on the door. She tried again and again to move that handle, swearing and praying desperately, but it would not be moved. She looked at the boy, and the boy looked at her, like prisoners destined to ride the lightning, accepting their fate, preparing themselves. The mother moved slowly across the hallway towards the drawing room, the sounds of the television booming from behind it, wishing this handle too would refuse to move. When it didn’t, she held her breath and slipped into the drawing room, closing the door behind her. The boy, overwhelmed, dropped to the kitchen floor and covered his ears as the shouting started, and the horrible rumbling of things being thrown, more terrified of what would come out of that room than whatever may come into the house from outside. Then, he felt stale air escape the drawing room in a great whoosh, and a claw of a hand seize him from the floor and carry him into the air. He pinned the boy to the wall and screamed into his face:

‘What have you done?! Huh?! Answer me, you stupid boy! What have you done?!’

His calloused hand smacked the boy across the face, making him see stars. He would’ve seen the night as well if the mother hadn’t come between them then, and begged the father to let the boy go. He did, but not gently. The boy fell to the hard floor and pain spread over his lower body. He screamed, but no one paid any attention to him. The father was on the phone, pushing the mother away if she tried to intervene. He made two calls. The first was to the police, who were no help, only offering to swing by in the morning if they still needed them to. They were needed in the city. The second call was to a locksmith, who also couldn’t come until morning. Even when they were offered double, triple the rate even. Tradesman didn’t come out this late, not with a van full of tools for the taking. There was no third call.

The boy crawled up off of the floor, only to be seized again, by the hair this time. The father swung him over to the foot of the stairs, directly opposite the front door, and dropped him on the step.

‘Get comfortable, you little shit!’ he barked at the boy. ‘You’re gonna sit there all damn night and keep watching that door! You hear me?! Otherwise, we’re all dead! You hear me? Dead!’

The mother quivered from behind him, tensely looking between man and boy. She went to say something but then stopped herself. The boy gave a tearful, blubbering “yes”, and the father was back in the drawing room again. She came and sat down beside him, slowly and carefully stroking his hair as he continued to cry in short, laboured bursts. When he finally tired himself out, he looked at her, and her face was stoical, forcing a smile. But he could tell that it was the sort used to calm the nerves of children, and maybe adults too. It would not do; they all knew something was coming. Eventually she couldn’t keep up the façade, and retreated to the kitchen to make them dinner – even the boy, especially the boy. If he was to keep watch tonight then he would need all his strength, but tomorrow he could expect to go without. They all ate in separate rooms, the boy ate his on the stairs.

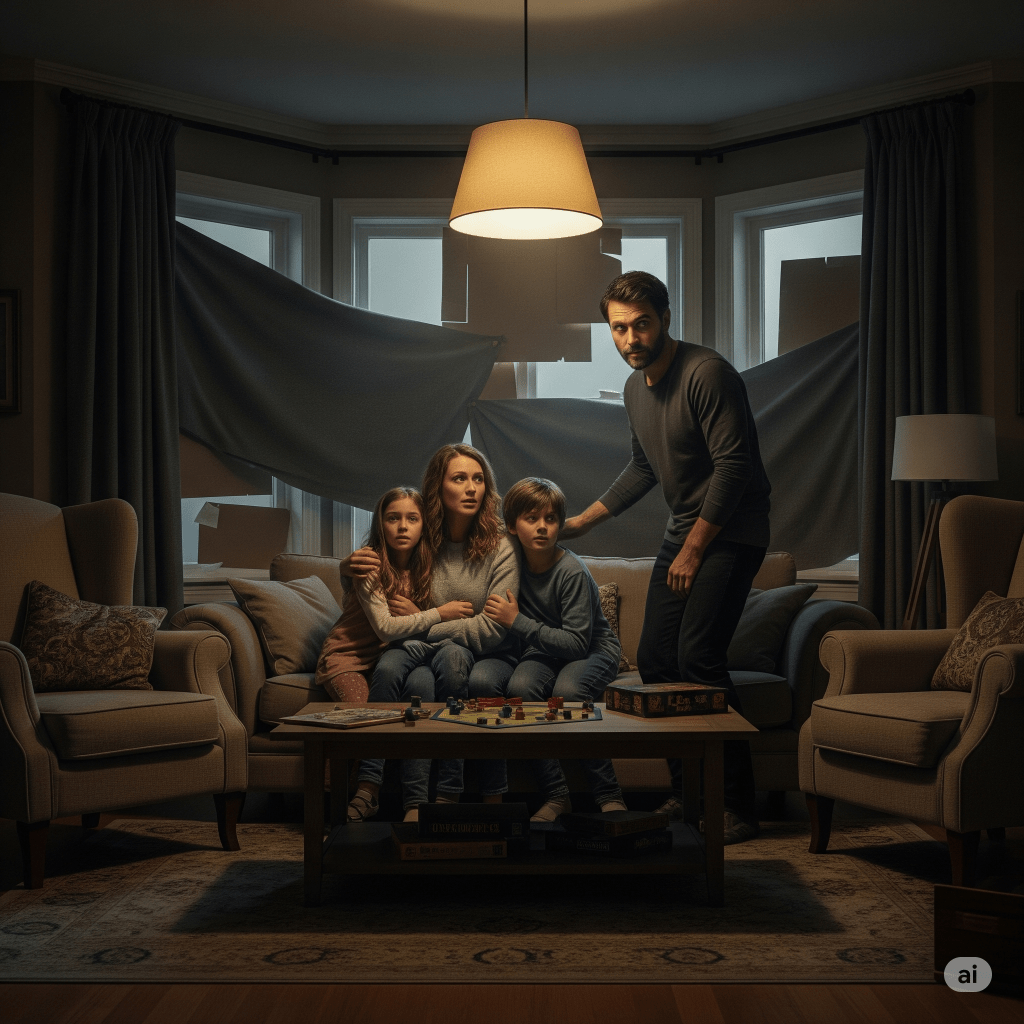

When the father had simmered down to something resembling calm, he came out of the drawing room and rounded up the others. He paced the hallway, anxiously, wringing his hands and periodically looking out of the window.

‘I will take the drawing room,’ he informed them. ‘I can see the back door from there in case they try that way.’

They. He kept saying it. They. Like he knew who they were and what they planned to do. It was no use arguing otherwise. In his mind, an armada of knife-wielding thugs were coming to attack the house that night, and the police would only come once they were at the door. He had spent another hour arguing on the phone with them, and despite his reminders of who exactly paid their salaries, they kept telling him that they wouldn’t come out unless a crime was in progress.

‘Your mother will stay upstairs,’ he continued. ‘She can see from the side of the house in case they decide to climb up into the house.’

This was ridiculous of course; the reason why climbing out of the windows to retrieve the keys wasn’t an option was because the father had sealed them shut.

‘Why don’t I sit down here instead?’ she asked, hints of desperation in her voice. ‘I don’t want him down here on his own, and he’ll be much safer upstairs.’

‘The boy stays here!’ he barked at her, right up in her face. ‘It’s his fault we’re in this mess in the first place.’

He looked down at the boy and sneered, shaking his head. There was silence after that, although he remained there for a moment to see his wife go reluctantly up the stairs.

‘Call me if you need anything, sweetie,’ she said, but the boy wasn’t listening. He was looking at his father, who was looking straight through him.

‘Anything happens to her, and it’s on you.’

‘I’m sorry, Dad. I’m really…’

‘Shut it!’ he spat, and skulked back to the drawing room again.

The boy sat facing the door, blackness staring back at him from the window. He imagined the terror and carnage unfolding in the streets of the city, and what would come out of it. I will keep watch and protect her, he insisted. I won’t let them come for her. The moment I see anything at the door, I’ll scream. I’ll scream and scream and won’t let them come. I’ll throw myself in front of her if I need to. I won’t let them. Won’t let them.

But when something did come to the door, the boy would not scream. He would see it and would feel fear the likes of which he’d never felt, but he would not scream. Hours went by, and the boy sat and watched. Even when his body tired out and sleep felt like the easiest thing to do, he forced himself to stay awake, stay alert. Twilight passed and a new day finally reared its head. The dawn pressed its blue face against the frosted glass and the boy sat up, staring towards the door, quiet. If this was a dream it was an unkind one, for the moment his eyes went towards it, he was paralysed, at its mercy. Whatever was coming for him had all the time in the world, whereas the boy only had the rest of his life.

Something moved across the threshold of the door and its shadow rose over the glass, perfectly silent. Its shape appeared human for the most part, but the way it moved was almost fluid-like, as if steam were pressing up against the glass. The boy wanted to scream but all he found were whimpers, and whatever was out there sensed it in him. Somehow, the boy knew that. The two could feel each other’s minds between the threshold. Something like an arm gave rise and trickled over the handle of the door, probing softly at the lock. The thin sound of metal slowly creaking brought the boy out of his stupor, and he knew at that moment he could finally scream if he wanted to, but didn’t. Screams would put his mother in danger, but he had to do something. So he stood up, and nearly fell back down again as the feeling had left his legs, but he steadied, and stepped onto the landing. The thing was still at the door, still trying to get in, its blank face staring at him through the frosted window. The boy crept slowly, silently, across the landing and backed towards the drawing room, keeping his eyes on the front door. He felt the wall at his back and reached for the door handle, squeezed it, and tried to open it but found the door was locked. He looked away from the hallway and tried the handle again but it wouldn’t open – his father had locked himself away. The boy was on his own.

He looked back towards the front door, and the thing was staring straight at him. It knew somehow that he was alone and that no help was coming, but still it did not enter, even though it could at any time. Instead it only stared, eyeless and uncaring, into the hallway, before eventually it seemed to fade away, leaving only a patch of fog against the window. Then, the boy was well and truly alone. He went and sat on the stairs again, and soon after fell asleep.

About an hour later, he awoke to the sound of metal hitting the ground outside. The boy fell back against the step and let out a groan, but nothing was moving around him. The door was still closed and presumably locked. An arm reached out from behind him and touched his cold skin, making him squirm and panic and nearly let out a scream. But it was only his mother, and she shushed him to be quiet while she held him in her arms. Instead of screaming, he broke into stifled sobs and buried his face against her bosom. She held him tightly, sitting with him on the stairs, and eventually they were both asleep again in each other’s arms.

Sunlight woke him again, filling the hallway with light that promised salvation. The boy wriggled free from his mother, who continued snoozing on the step, and got up. He felt a strange urge to try for the front door, even though he knew it to be locked. Something else inside his mind told him it was not, and it was okay to go towards it. He did so, as if pulled across the hallway by invisible strings, and placed his hand around the cold, metal handle. There was strength in him that appeared to come from nowhere as he pulled the handle down, and without any resistance at all, the door opened. Warm, summer air caressed him at the threshold as he stared out into the quiet street, where no one and no thing waited for him. And then the sunlight reflected off something and caught his eye, just for a moment, and he looked down. The keys! The keys were sitting there on the doorstep, as if placed there, and he remembered the clanging of metal in the night and knew at once what had caused it, but not how.

The boy reached down and took the keys in hand, the metal warmed by sunlight. He looked over the quiet street again and sighed when the hand came down on his shoulder. This time he did not flinch. He knew it was her.

‘Give those to me,’ his mother told him, before looking over her shoulder into the hallway. When she was satisfied that the drawing room door would not open, she stepped out into the street with her son and gently closed the door behind them, locking it again.

‘Where are we going, Mama?’

‘In the car,’ she told him. ‘But you must promise me something first.’

The boy nodded, gazing up at her.

‘Wherever we go,’ she said, ‘don’t leave the keys in the door .’