“Gray hair is a crown of glory; it is gained in a righteous life.”

Proverbs, 16:31

One day – sooner than you think – you will get old. We frequently push this fact to the back of our minds. We don’t like to think about losing our hair. About our bodies breaking down. And we certainly don’t like to dwell on the loneliness that often comes with old age. Our elders represent our future. That’s why we avoid listening to them, and why we so desperately need to listen to them. Our ignorance shows. We are so often incapable of talking to old people properly. We patronise them. We treat them like children. We regard their opinions as inferior to our own, suggesting they should have less of a say in our future than we do. Well just who do you think secured that future for us? Who do you think sacrificed life and limb for our right to rights? Who worked long hours, under horrible bosses and glass ceilings for us to grow up? Let me put it another way. Would you think it fair, that after a long life of paying taxes and raising the next generation of workers, for your voice to be disregarded? Silenced even. No. It’s a despicable notion. And yet we’ve allowed it to perpetuate. What we should be doing instead is listening to our elders. For everything that has ever happened or will happen to you, has already happened to countless others in a variety of different ways.

Let’s take some inspiration from the past then. In Norse mythology, Mímisbrunnr (Mimir’s Well), is a source of great wisdom at the roots of Yggdrasill, the world tree. Odin pledged one of his own eyes in order to drink from the waters and receive sapience. In our own world, we too have access to an extraordinary source of wisdom, in the form of our older generations. We must also pledge something in return for this, but it need not be as severe as losing an eye. The pledge we make, is our time. Which, although precious, is not painful to give up. And yet we gather a treasure nonetheless. We gain their collective experience without ever having lived their lives. This can be invaluable, and also immeasurably kind. Lest we forget that our elders are also human beings, and as such deserve dignity and respect. Yet we abandon them to their fate. There’s a bona fide uproar whenever a library is closed down, and rightly so. But the same cannot be said when the old, arguably our greatest source of knowledge, are written off and condemned to isolation for their remaining years. We need to do better than this. Myself included.

I was raised as a Christian. When I was fifteen, my faith was broken and I became an atheist. After that, I was constantly challenging my parents’ views over what I perceived to be ignorance, a rejection of reality. I remember asking my father, “Why did you raise me as a Christian?”, to which he replied that it was “better than the alternative”. The alternative was believing in nothing. I shrugged this off at the time, taking it as an unfair criticism of unbelievers. But his words echo louder and louder as I grow older myself. And although my faith has not been entirely restored, I understand his reasoning now. Christianity encourages one to discover the truth outside themselves, assert value to all of human life, to pursue what is meaningful, and design boundaries for sexual activity. These are values which I have returned to in my adult life, and ones I believe to be beneficial to the whole of society. This is not to say that we should live our lives according to scripture, or even believe in God for that matter. But the fact remains that we require a moral compass from an early age, and that it is far easier to implement one with the aid of supernatural reinforcement. After all, we teach children that they should behave for Santa Claus, that they should go to sleep for the Tooth Fairy, and so on. I don’t wish to offend the religious by saying this. There are many temptations offered to us in life, and a commitment to the divine is often a good means of resisting them. My parents have many beliefs that I didn’t agree with initially. But as I’ve grown and experienced the world for myself, my views have changed. And so I was wrong, but I owe my parents no apology. Above else, they wanted me to think for myself, to find meaning in life, and to always try to be kind. On all counts, they have succeeded.

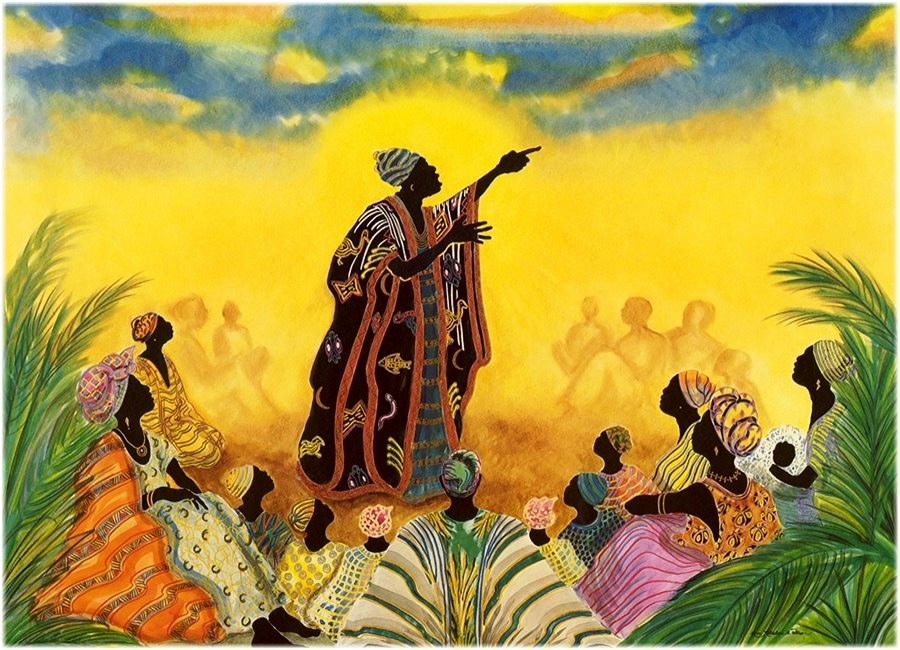

We are destined to replace our older generations, and as such we are required to carry their knowledge forth. This is regarded more highly in some cultures. For example, in many West African societies, there exist living repositories of the oral tradition, known as Griots. They act as archives for their people’s history, traditions, and culture. Although performers, the Griots are highly respected and are regarded as leaders in their communities. They may seem somewhat redundant in an age where anything and everything can be simply Googled, but we often neglect the more human side to our history. That’s where the art of storytelling comes in.

I recently had a conversation with a woman of ninety-one years, who inspired me to write this article. She recounted not only her own experiences, but those of her elders as well. She told me stories of Britain at war, through the eyes of human beings, not the pages of history books:

Second Boer War 1899-1902

Her grandfather was a young lieutenant, fighting in South Africa. She described him as “the meanest bastard there ever was”, with “cold, grey eyes”. In the thick of the fighting, across the scorched earth of the Boer homelands, he commanded a troop of around thirty men. The British Army had set up concentration camps for civilian families, tens of thousands of whom went on to die from disease and starvation. A true testament to the evil mankind is capable of. One day, the young lieutenant stepped into one of these camps. They were poorly constructed and severely overcrowded. Hygiene was pitiful. Sickness was rife. Food rations were meagre – even for the British. There came a point when his own men were contemplating mutiny. Such chaos, such human horror. So many voices calling out for deliverance, for leadership, for the sweet embrace of death. The young lieutenant froze. He did the only thing he could in that moment. He walked away. He walked and walked and walked – waiting for someone to stop him. But no one did. Anyone who could have was either dead or dying. He walked all the way to the shoreline, where he commandeered a ship. Again, no one stopped him. The lieutenant set sail across the Atlantic, as he had when he was a boy, and never looked back.

WWI 1914-1918

Twelve years after the conflict with the Boers, the entire world was plunged into war. Millions of Britons enlisted in the fight against the Central Powers. Among them, was a young man of seventeen, the son of the lost lieutenant. Although he hadn’t seen or heard from his father in over a decade, he was compelled to fight all the same. He made his way to Liverpool, where the recruits were being drilled. Upon stepping off the train, he was met with familiar eyes. Grey eyes. Belonging to the meanest bastard there ever was. The British Army had offered to pardon any former deserters if they offered to train new recruits, so his father had accepted the call. When they came face-to-face, it was not the reunion he had hoped for. Knowing the boy to be under-age, the lieutenant beat him within an inch of his life. Right there on the platform! In front of his men. In front of the boy’s friends. Then he put him back on the train, and sent him home. That was the last he saw of his father, but not the last he saw of war.

He went on to enlist again, and soon found himself on the Western Front. Along the trench lines, surrounded by mud and wire, he was tasked with halting the German advance into France. It was there that he was captured. He would later recount to his daughter the terror he felt, cowering in a shallow crater in no-man’s-land, his dead friends around him, a German solider pointing his rifle at him. He could’ve just as easily killed him. But he didn’t. It’s a stark reminder that not all Germans were evil. The majority of soldiers were just men, fighting another man’s cause. They put him to work chopping trees. He was good at it, but only because he’d be killed otherwise. When the war was over, they offered him a place among them. He chose to return home instead, where he started a family. Because of that decision, these stories found their way to me.

WWII 1939-1945

When the world broke out in war again, his daughter was but a schoolgirl. She remembers the men leaving and waving their families goodbye. The bombs falling. Churchill’s voice on the radio. Her school being destroyed. But mostly she remembers the men who came back, and how different they were when they did. Her future husband had been one of those who had fought. He had also been captured, so she never really met the man he was before the war. She went on to witness a lot of conflict in her life. Enough to know that war only ever seems to benefit the powerful. The soldiers, the people, are seldom remembered. We’ll never hear most of their stories. When she told me this, I promised her that I would try.

More than ever, we need the wisdom and the stories of our elders. They shape many of the attitudes and values we pass on to future generations. Life is full of conflicts. And if we take our elders for granted, we’ll have no foundation to rebuild upon. As the Italian philosopher George Santayana once said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” So listen to your elders. Chances are they know something you don’t.

To enquire about republishing my content, please email me at crstrang.info@gmail.com.