Hype ruins everything these days. I remember sitting through three of most anticipated films of the last year – Avengers: Endgame, Joker, and The Irishman – and my response to all three of them was a resounding “meh”. They were not bad films by any means, but they all shared one thing in common: they were hyped up beyond belief. Each one had been accompanied by a barrage of social media posts, online articles, and discussions among chattering cinephiles, who hailed them all as the biggest, boldest, and most iconic films of the year. The hoopla around films begins at pre-production these days. And it always feels excessive. It’s like starting an avalanche with an iceberg. By the time you take your seats, the hype has far surpassed any standard the film could possibly live up to. And so the result is always somewhat underwhelming.

This isn’t exclusive to films. We overrate basically everything now. TV shows, video games, studio albums – anything that sells. We’re constantly spoon-fed anticipation by marketing companies. And we fall for it every time. They take our money, and we often get a mouthful of cold, slimy mush in return. The worst thing about hype is that it robs you of your opinion, as your experience is constantly weighted against expectation. There’s nothing organic to your own reaction anymore. Even as I sit here writing this, I’m wondering whether this article will be better than my last. Spoiler alert: it probably won’t be. But maybe I’ll surprise myself. In a culture obsessed with hype, being surprised would be a very welcome thing.

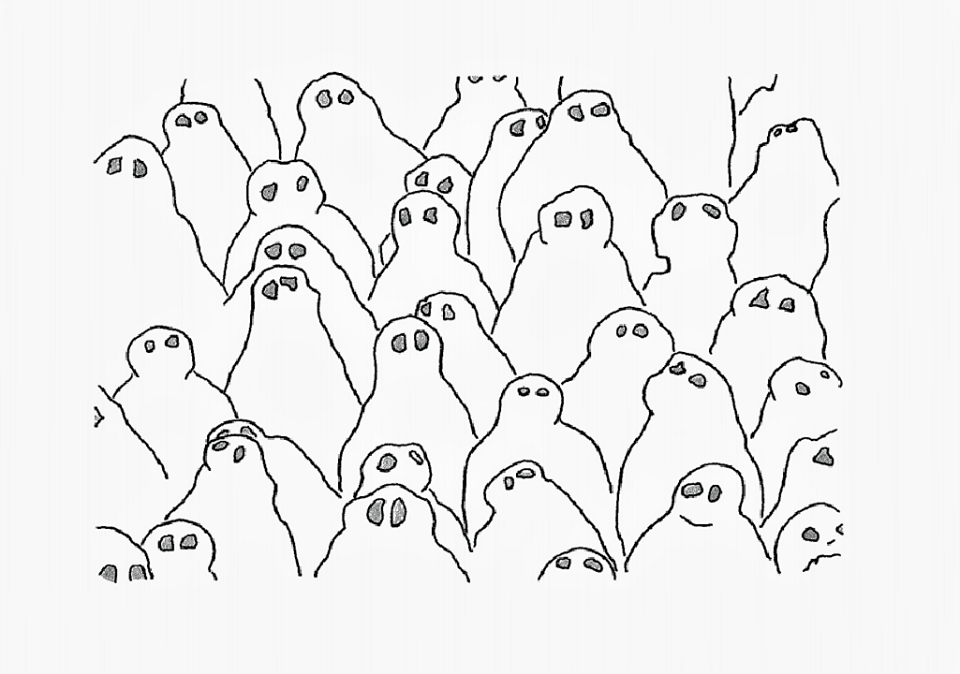

When Field for the British Isles, an installation piece by Antony Gormley, comprising around 40,000 small clay figures, came to Colchester, it’s fair to say the hype was real. Where to begin… Antony Gormley is a household name in the art community. He’s known the world over for such ambitious works as Angel of the North, Event Horizon, and Quantum Cloud. In 1994, Gormley won the Turner Prize, with Field playing a crucial role in securing it. Since then, the work has been installed and displayed at various locations around the globe, and is the largest single work in the Arts Council Collection. Sounds impressive, eh? I thought so too.

In the weeks leading up to its installation, that’s all anyone could talk about. The mere mention of it was enough to send people into fits of exhilaration. The hype train was moving quickly across the tracks, with no signs of slowing. Even the building that was to house it had to undergo its most ambitious renovation to date. The gallery was completely transformed, and the onlooking public were expecting big things. Then the installment of the 40,000 individual terracotta figures began, with scores of local volunteers signed up to do it. They gave interviews between shifts about just how vast and iconic it was going to be. Pretty soon the launch was looming. The brakes were off. Nothing was stopping this train.

I became overexcited, my head buzzing with anticipation right up to the moment they announced it was ready to view. I strolled up to the gallery with a spring in my step. The first thing I noticed was Gormley’s name in huge lettering upon the wall going in. Then I finally reached the exhibition, and all at once the hype train came crashing into the back of me. As I beheld the 40,000 tiny clay figures, looking up at me with their 80,000 piercing eyes, my response was simply: “Meh”. And then I went home.

Field had failed to impress me. I wasn’t angry about it. I’ve become desensitised to a lot of things, and disappointment’s one of them. I went back to the gallery several times after the launch, desperate to capture some of the magic that I was promised. The spell seemed to be working on everyone else. All but me had some kind of response. Most people had uniformed reactions of wonder. Some burst into tears. Others broke out in riant smiles. There was the odd negative reaction too. Some were unsettled by it. And one chap even stuck two fingers up at it, angrily decrying it a waste of taxpayer’s money. Fair enough. Those are at least genuine, emotional reactions. All I could muster was a measly “meh”. Soon enough, I became benumbed to the entire exhibition. No longer even impressed by it’s sheer scale. Or the community effort that had been poured into it.

Many years ago, I worked in a care home for the elderly. One thing you get used to pretty quickly is people dying. It gets to the point where you don’t even feel saddened by it anymore. But every once in a while, a genuine feeling emerges. You remember something about the departed. Something small. A smile they gave you. A conversation you had with them. It unexpectedly pulls at your heartstrings. Something similar happened in the gallery one day, and came in the form of a question:

A visitor approached me, all red in the cheeks like a Plum-faced Lorikeet. They asked me, as I looked out over the carpet of gormless, clay faces, “What do you think?”

I gave a packaged reply.

“The idea is that the viewer is God.” I answered them, (basically quoting Gormley himself). “They’re asking us what kind of world we’re making.”

“I know that.” they replied. “I’m asking what you think of it.”

I was slightly taken aback by this. No one had asked me for my own opinion on it. Plenty had given me theirs, and the vast majority had been painfully predictable. But when it came to my own, I knew I had to think of something more than simply “meh”. So I told them everything I’ve just told you. And they listened. By the time I had finished speaking, I finally realised the point of the exhibition.

Field is about individualism. Each of the 40,000 figures were handcrafted by ordinary people. The effect wouldn’t be the same if they were mass-produced. But the focus of the artwork was never the terracotta figures. It was and always will be, the viewer. Field is a celebration of individualism. Now, Gormley describes the artwork as such, so this isn’t any kind of revelation. But the reason why this resonates so deeply for me seems to actively go against the consensus of our time. The artwork celebrates individualism in an age of groupthink. Our culture is obsessed with identity, and we are often hostile to those who step outside their boxes. But consider for a moment, that maybe Field was made, but not intended for, the 1% of us who dared to challenge its genius. There’s a strange irony to it when you think about it. An exhibition about individualism, where the majority of people have the same reaction. It’s actually quite funny. And in that moment of realisation, I had my first, genuine reaction to Field. I laughed. It was starting to grow on me. Field is a victim of its own success in many ways. It was so over-hyped that people’s impressions of it were formed long before they saw it – which somewhat undercuts the point.

I’ll be returning to this exhibition soon, but not to see the artwork. Instead I want to watch how people react to it. To see if I can spot any fellow dissidents who don’t see what all the fuss is about. It’s them I’d like to talk to, more than anyone else. You should go and see Field for yourself. But please, lower your expectations. Not because it’s lacking in quality, but because you owe it to your own opinion to not believe the hype.

To enquire about republishing my content, please email me at crstrang.info@gmail.com.